Chapter 4: Anxiety Disorders

4.1 Anxiety and Related Disorders

David H. Barlow; Kristen K. Ellard; Jorden A. Cummings; Kendall Deleurme; and Jessica Campoli

Section Learning Objectives

- Understand the relationship between anxiety and anxiety disorders.

- Identify key vulnerabilities for developing anxiety and related disorders.

- Identify main diagnostic features of specific anxiety-related disorders.

- Differentiate between disordered and non-disordered functioning.

- Describe treatments for anxiety disorders

What is Anxiety?

What is anxiety? Most of us feel some anxiety almost every day of our lives. Maybe you have an important test coming up for school. Or maybe there’s that big game next Saturday, or that first date with someone new you are hoping to impress. Anxiety can be defined as a negative mood state that is accompanied by bodily symptoms such as increased heart rate, muscle tension, a sense of unease, and apprehension about the future (APA, 2013; Barlow, 2002).

Anxiety is what motivates us to plan for the future, and in this sense, anxiety is actually a good thing. It’s that nagging feeling that motivates us to study for that test, practice harder for that game, or be at our very best on that date. But some people experience anxiety so intensely that it is no longer helpful or useful. They may become so overwhelmed and distracted by anxiety that they actually fail their test, fumble the ball, or spend the whole date fidgeting and avoiding eye contact. If anxiety begins to interfere in the person’s life in a significant way, it is considered a disorder.

Vulnerabilities to Anxiety

Anxiety and closely related disorders emerge from “triple vulnerabilities,”a combination of biological, psychological, and specific factors that increase our risk for developing a disorder (Barlow, 2002; Suárez, Bennett, Goldstein, & Barlow, 2009). Biological vulnerabilities refer to specific genetic and neurobiological factors that might predispose someone to develop anxiety disorders. No single gene directly causes anxiety or panic, but our genes may make us more susceptible to anxiety and influence how our brains react to stress (Drabant et al., 2012; Gelernter & Stein, 2009; Smoller, Block, & Young, 2009). Psychological vulnerabilities refer to the influences that our early experiences have on how we view the world. If we were confronted with unpredictable stressors or traumatic experiences at younger ages, we may come to view the world as unpredictable and uncontrollable, even dangerous (Chorpita & Barlow, 1998; Gunnar & Fisher, 2006). Specific vulnerabilities refer to how our experiences lead us to focus and channel our anxiety (Suárez et al., 2009). If we learned that physical illness is dangerous, maybe through witnessing our family’s reaction whenever anyone got sick, we may focus our anxiety on physical sensations. If we learned that disapproval from others has negative, even dangerous consequences, such as being yelled at or severely punished for even the slightest offense, we might focus our anxiety on social evaluation. If we learn that the “other shoe might drop” at any moment, we may focus our anxiety on worries about the future. None of these vulnerabilities directly causes anxiety disorders on its own—instead, when all of these vulnerabilities are present, and we experience some triggering life stress, an anxiety disorder may be the result (Barlow, 2002; Suárez et al., 2009). In the next sections, we will briefly explore each of the major anxiety-based disorders, found in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (APA, 2013).

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Most of us worry some of the time, and this worry can actually be useful in helping us to plan for the future or make sure we remember to do something important. Most of us can set aside our worries when we need to focus on other things or stop worrying altogether whenever a problem has passed. However, for someone with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), these worries become difficult, or even impossible, to turn off. They may find themselves worrying excessively about a number of different things, both minor and catastrophic. Their worries also come with a host of other symptoms such as muscle tension, fatigue, agitation or restlessness, irritability, difficulties with sleep (either falling asleep, staying asleep, or both), or difficulty concentrating.The DSM-5 criteria specify that at least six months of excessive anxiety and worry of this type must be ongoing, happening more days than not for a good proportion of the day, to receive a diagnosis of GAD.

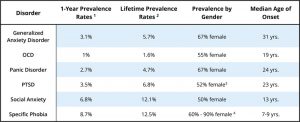

About 5.7% of the population has met criteria for GAD at some point during their lifetime (Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005), making it one of the most common anxiety disorders (see Table 1). Data from the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey found that the 12-month and lifetime prevalence rate of GAD for Canadians aged 15 or older was 2.6% and 8.7%, respectively (Statistics Canada, 2016). GAD has been found more commonly among women and in urban geographical areas (Pelletier, O’Donnell, McRae, & Grenier, 2017).

What makes a person with GAD worry more than the average person? Research shows that individuals with GAD are more sensitive and vigilant toward possible threats than people who are not anxious (Aikins & Craske, 2001; Barlow, 2002; Bradley, Mogg, White, Groom, & de Bono, 1999). This may be related to early stressful experiences, which can lead to a view of the world as an unpredictable, uncontrollable, and even dangerous place. Some have suggested that people with GAD worry as a way to gain some control over these otherwise uncontrollable or unpredictable experiences and against uncertain outcomes (Dugas, Gagnon, Ladouceur, & Freeston, 1998). By repeatedly going through all of the possible “What if?” scenarios in their mind, the person might feel like they are less vulnerable to an unexpected outcome, giving them the sense that they have some control over the situation (Wells, 2002). Others have suggested people with GAD worry as a way to avoid feeling distressed (Borkovec, Alcaine, & Behar, 2004). For example, Borkovec and Hu (1990) found that those who worried when confronted with a stressful situation had less physiological arousal than those who didn’t worry, maybe because the worry “distracted” them in some way.

The problem is, all of this “what if?”-ing doesn’t get the person any closer to a solution or an answer and, in fact, might take them away from important things they should be paying attention to in the moment, such as finishing an important project. Many of the catastrophic outcomes people with GAD worry about are very unlikely to happen, so when the catastrophic event doesn’t materialize, the act of worrying gets reinforced (Borkovec, Hazlett-Stevens, & Diaz, 1999). For example, if a mother spends all night worrying about whether her teenage daughter will get home safe from a night out and the daughter returns home without incident, the mother could easily attribute her daughter’s safe return to her successful “vigil.” What the mother hasn’t learned is that her daughter would have returned home just as safe if she had been focusing on the movie she was watching with her husband, rather than being preoccupied with worries. In this way, the cycle of worry is perpetuated, and, subsequently, people with GAD often miss out on many otherwise enjoyable events in their lives.

Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia

Have you ever gotten into a near-accident or been taken by surprise in some way? You may have felt a flood of physical sensations, such as a racing heart, shortness of breath, or tingling sensations. This alarm reaction is called the “fight or flight” response (Cannon, 1929) and is your body’s natural reaction to fear, preparing you to either fight or escape in response to threat or danger. It’s likely you weren’t too concerned with these sensations, because you knew what was causing them. But imagine if this alarm reaction came “out of the blue,” for no apparent reason, or in a situation in which you didn’t expect to be anxious or fearful. This is called an “unexpected” panic attack or a false alarm. Because there is no apparent reason or cue for the alarm reaction, you might react to the sensations with intense fear, maybe thinking you are having a heart attack, or going crazy, or even dying. You might begin to associate the physical sensations you felt during this attack with this fear and may start to go out of your way to avoid having those sensations again.

Unexpected panic attacks such as these are at the heart of panic disorder (PD). However, to receive a diagnosis of PD, the person must not only have unexpected panic attacks but also must experience continued intense anxiety and avoidance related to the attack for at least one month, causing significant distress or interference in their lives. People with panic disorder tend to interpret even normal physical sensations in a catastrophic way, which triggers more anxiety and, ironically, more physical sensations, creating a vicious cycle of panic (Clark, 1986, 1996). The person may begin to avoid a number of situations or activities that produce the same physiological arousal that was present during the beginnings of a panic attack. For example, someone who experienced a racing heart during a panic attack might avoid exercise or caffeine. Someone who experienced choking sensations might avoid wearing high-necked sweaters or necklaces. Avoidance of these internal bodily or somatic cues for panic has been termed interoceptive avoidance (Barlow & Craske, 2007; Brown, White, & Barlow, 2005; Craske & Barlow, 2008; Shear et al., 1997).

The individual may also have experienced an overwhelming urge to escape during the unexpected panic attack. This can lead to a sense that certain places or situations—particularly situations where escape might not be possible—are not “safe.” These situations become external cues for panic. If the person begins to avoid several places or situations, or still endures these situations but does so with a significant amount of apprehension and anxiety, then the person also has agoraphobia (Barlow, 2002; Craske & Barlow, 1988; Craske & Barlow, 2008). Agoraphobia can cause significant disruption to a person’s life, causing them to go out of their way to avoid situations, such as adding hours to a commute to avoid taking the train or only ordering take-out to avoid having to enter a grocery store. In one tragic case seen by our clinic, a woman suffering from agoraphobia had not left her apartment for 20 years and had spent the past 10 years confined to one small area of her apartment, away from the view of the outside. In some cases, agoraphobia develops in the absence of panic attacks and therefore is a separate disorder in DSM-5. But agoraphobia often accompanies panic disorder.

One third of adults in Canada experience a panic attack each year; however, only 1-2% of Canadians that same year are diagnosed with panic disorder (Canadian Mental Health Association’s BC Division, 2013). About 4.7% of the population has met criteria for PD or agoraphobia over their lifetime, according to both American (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005; Kessler et al., 2006) (see Table 4.1) and Canadian data (Canadian Mental Health Association’s BC Division, 2013). In all of these cases of panic disorder, what was once an adaptive natural alarm reaction now becomes a learned, and much feared, false alarm. Data from the 2002 Canadian Community Health Survey found that the prevalence of agoraphobia was 0.78% for people aged 15-54 years and 0.61% for adults aged 55 years or older (McCabe, Cairney, Veldhuizen, Herrmann, & Streiner, 2006). In that paper, agoraphobia was reported to be more common in women, younger age groups, and people who were widowed or divorced (McCabe et al., 2006).

Specific Phobia

The majority of us might have certain things we fear, such as bees, or needles, or heights (Myers et al., 1984). But what if this fear is so consuming that you can’t go out on a summer’s day, or get vaccines needed to go on a special trip, or visit your doctor in her new office on the 26th floor? To meet criteria for a diagnosis of specific phobia, there must be an irrational fear of a specific object or situation that substantially interferes with the person’s ability to function. For example, a patient at our clinic turned down a prestigious and coveted artist residency because it required spending time near a wooded area, bound to have insects. Another patient purposely left her house two hours early each morning so she could walk past her neighbor’s fenced yard before they let their dog out in the morning. Specific phobias affect about 1 in every 10 Canadians (Canadian Psychological Association, 2015).

The list of possible phobias is staggering, but four major subtypes of specific phobia are recognized: blood-injury-injection (BII) type, situational type (such as planes, elevators, or enclosed places), natural environment type for events one may encounter in nature (for example, heights, storms, and water), and animal type.

A fifth category “other” includes phobias that do not fit any of the four major subtypes (for example, fears of choking, vomiting, or contracting an illness). Most phobic reactions cause a surge of activity in the sympathetic nervous system and increased heart rate and blood pressure, maybe even a panic attack. However, people with BII type phobias usually experience a marked drop in heart rate and blood pressure and may even faint. In this way, those with BII phobias almost always differ in their physiological reaction from people with other types of phobia (Barlow & Liebowitz, 1995; Craske, Antony, & Barlow, 2006; Hofmann, Alpers, & Pauli, 2009; Ost, 1992). BII phobia also runs in families more strongly than any phobic disorder we know (Antony & Barlow, 2002; Page & Martin, 1998). Specific phobia is one of the most common psychological disorders in the United States, with 12.5% of the population reporting a lifetime history of fears significant enough to be considered a “phobia” (Arrindell et al., 2003; Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005) (see Table 1). Most people who suffer from specific phobia tend to have multiple phobias of several types (Hofmann, Lehman, & Barlow, 1997).

Social Anxiety Disorder (Social Phobia)

Many people consider themselves shy, and most people find social evaluation uncomfortable at best, or giving a speech somewhat mortifying. Yet, only a small proportion of the population fear these types of situations significantly enough to merit a diagnosis of social anxiety disorder (SAD) (APA, 2013). SAD is more than exaggerated shyness (Bogels et al., 2010; Schneier et al., 1996). To receive a diagnosis of SAD, the fear and anxiety associated with social situations must be so strong that the person avoids them entirely, or if avoidance is not possible, the person endures them with a great deal of distress. Further, the fear and avoidance of social situations must get in the way of the person’s daily life, or seriously limit their academic or occupational functioning. For example, a patient at our clinic compromised her perfect 4.0 grade point average because she could not complete a required oral presentation in one of her classes, causing her to fail the course. Fears of negative evaluation might make someone repeatedly turn down invitations to social events or avoid having conversations with people, leading to greater and greater isolation.

The specific social situations that trigger anxiety and fear range from one-on-one interactions, such as starting or maintaining a conversation; to performance-based situations, such as giving a speech or performing on stage; to assertiveness, such as asking someone to change disruptive or undesirable behaviors. Fear of social evaluation might even extend to such things as using public restrooms, eating in a restaurant, filling out forms in a public place, or even reading on a train. Any type of situation that could potentially draw attention to the person can become a feared social situation. For example, one patient of ours went out of her way to avoid any situation in which she might have to use a public restroom for fear that someone would hear her in the bathroom stall and think she was disgusting. If the fear is limited to performance-based situations, such as public speaking, a diagnosis of SAD performance only is assigned.

What causes someone to fear social situations to such a large extent? The person may have learned growing up that social evaluation in particular can be dangerous, creating a specific psychological vulnerability to develop social anxiety (Bruch & Heimberg, 1994; Lieb et al., 2000; Rapee & Melville, 1997). For example, the person’s caregivers may have harshly criticized and punished them for even the smallest mistake, maybe even punishing them physically.

Or, someone might have experienced a social trauma that had lasting effects, such as being bullied or humiliated. Interestingly, one group of researchers found that 92% of adults in their study sample with social phobia experienced severe teasing and bullying in childhood, compared with only 35% to 50% among people with other anxiety disorders (McCabe, Antony, Summerfeldt, Liss, & Swinson, 2003). Someone else might react so strongly to the anxiety provoked by a social situation that they have an unexpected panic attack. This panic attack then becomes associated (conditioned response) with the social situation, causing the person to fear they will panic the next time they are in that situation. This is not considered PD, however, because the person’s fear is more focused on social evaluation than having unexpected panic attacks, and the fear of having an attack is limited to social situations. According to American studies, as many as 12.1% of the general population suffer from social phobia at some point in their lives (Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005), making it one of the most common anxiety disorders, second only to specific phobia (see Table 1). In a survey of residents (aged 15-64) from Ontario, Canada, the 12-month and lifetime prevalence of social anxiety was 6.7% and 13%, respectively (Stein & Kean, 2000). Social anxiety disorder is more common among females and younger age groups (Stein & Kean, 2000).

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Have you ever had a strange thought pop into your mind, such as picturing the stranger next to you naked? Or maybe you walked past a crooked picture on the wall and couldn’t resist straightening it. Most people have occasional strange thoughts and may even engage in some “compulsive” behaviors, especially when they are stressed (Boyer & Liénard, 2008; Fullana et al., 2009). But for most people, these thoughts are nothing more than a passing oddity, and the behaviors are done (or not done) without a second thought. For someone with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), however, these thoughts and compulsive behaviors don’t just come and go. Instead, strange or unusual thoughts are taken to mean something much more important and real, maybe even something dangerous or frightening. The urge to engage in some behavior, such as straightening a picture, can become so intense that it is nearly impossible not to carry it out, or causes significant anxiety if it can’t be carried out. Further, someone with OCD might become preoccupied with the possibility that the behavior wasn’t carried out to completion and feel compelled to repeat the behavior again and again, maybe several times before they are “satisfied.”

To receive a diagnosis of OCD, a person must experience obsessive thoughts and/or compulsions that seem irrational or nonsensical, but that keep coming into their mind. Some examples of obsessions include doubting thoughts (such as doubting a door is locked or an appliance is turned off), thoughts of contamination (such as thinking that touching almost anything might give you cancer), or aggressive thoughts or images that are unprovoked or nonsensical. Compulsions may be carried out in an attempt to neutralize some of these thoughts, providing temporary relief from the anxiety the obsessions cause, or they may be nonsensical in and of themselves. Either way, compulsions are distinct in that they must be repetitive or excessive, the person feels “driven” to carry out the behavior, and the person feels a great deal of distress if they can’t engage in the behavior. Some examples of compulsive behaviors are repetitive washing (often in response to contamination obsessions), repetitive checking (locks, door handles, appliances often in response to doubting obsessions), ordering and arranging things to ensure symmetry, or doing things according to a specific ritual or sequence (such as getting dressed or ready for bed in a specific order). To meet diagnostic criteria for OCD, engaging in obsessions and/or compulsions must take up a significant amount of the person’s time, at least an hour per day, and must cause significant distress or impairment in functioning.

According to large American samples, 1.6% of the population has met criteria for OCD over the course of a lifetime (Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005) (see Table 1). Data from the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey estimated the prevalence of OCD at 0.93%, and found that it was more common among females, younger adults, and those with lower incomes (Osland, Arnold, & Pringsheim, 2018). Although people with OCD, compared to people without OCD, are significantly more likely to report needing help for mental health, they are more likely to not actually receive help (Osland et al., 2018). There may be a potential gap between the needs of people with OCD symptoms and existing services. Whereas OCD was previously categorized as an Anxiety Disorder, in the most recent version of the DSM (DSM-5; APA, 2013) it has been reclassified under the more specific category of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders.

People with OCD often confuse having an intrusive thought with their potential for carrying out the thought. Whereas most people when they have a strange or frightening thought are able to let it go, a person with OCD may become “stuck” on the thought and be intensely afraid that they might somehow lose control and act on it. Or worse, they believe that having the thought is just as bad as doing it. This is called thought-action fusion. For example, one patient of ours was plagued by thoughts that she would cause harm to her young daughter. She experienced intrusive images of throwing hot coffee in her daughter’s face or pushing her face underwater when she was giving her a bath. These images were so terrifying to the patient that she would no longer allow herself any physical contact with her daughter and would leave her daughter in the care of a babysitter if her husband or another family was not available to “supervise” her. In reality, the last thing she wanted to do was harm her daughter, and she had no intention or desire to act on the aggressive thoughts and images, nor does anybody with OCD act on these thoughts, but these thoughts were so horrifying to her that she made every attempt to prevent herself from the potential of carrying them out, even if it meant not being able to hold, cradle, or cuddle her daughter. These are the types of struggles people with OCD face every day.

What is Eco-Anxiety?

An assessment conducted by the Government of Canada in 2019 analyzed climate data from 1948 to 2016, which confirmed what many expected but feared – a steady, linear progression of climate warming that is projected to amplify. Further, risks of extreme weather and climate-related natural disasters are increasingly widespread and are having serious consequences (Government of Canada, 2019). For Canadians, this includes increased exposure to wildfires (Jain et al., 2017), heatwaves (Hartmann et al., 2013), droughts (Girardin & Wotton, 2009), floods (Burn & Whitfield, 2015), snow and ice cover durations, freshwater availability, and changes in surrounding ocean activity in the coming years (as cited in Government of Canada, 2019). You may even recall some relatively recent disasters, such as the 2013 Southern Alberta flood and the 2016 Fort McMurray wildfire.

Historically, discussions and research on the impact of climate change primarily focused on physical health, such as increased risk of asthma and cardiovascular disease (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & National Center for Environmental Health, 2014). However, as Canadians continue to be affected by widespread climate change, interest in the effects of climate change on mental health has significantly increased (APA, 2017). For example, with exposure to climate change comes increased emotional responding, which can be debilitating (APA, 2017). Heightened emotional responses can disrupt individuals’ information processing and decision making, interfering with daily functioning (APA, 2017). Further, extreme weather and climate-related natural disasters can be traumatic, regardless if individuals experience them directly, further impairing mental health (APA, 2017). Researchers have demonstrated positive correlations between climate change and several mental health issues, including depression and substance use (Neria & Shultz, 2012), as well as posttraumatic stress (Bryant et al., 2014). Concerningly, climate change also appears to relate to increased aggression and interpersonal violence (Anderson, 2001; Ranson, 2012).

Have you ever found yourself worrying about these issues and the potential consequences for not only our current living, but also future generations? If so, you are not alone. Individuals of all ages are becoming increasingly worried and fearful about environmental damage and potential future disaster – this is something we refer to as eco-anxiety (Albrecht, 2011; American Psychological Association [APA], 2017). However, you may have heard other variations of this term, including ‘climate anxiety,’ ‘climate grief,’ and ‘environmental doom.’ Eco-anxiety is largely founded on the current state of the environment and its uncertain future. Additionally, given current evidence demonstrating the direct impact of humans on climate change (see Government of Canada, 2019, for a detailed review), those struggling with eco-anxiety are often primarily concerned about the role of human activities (APA, 2017). While data indicating the exact prevalence of eco-anxiety is limited, research based in Australia suggests that ~96% of young people consider climate change to be a serious issue and ~89% report being concerned about the long-term consequences (Chiw & Ling, 2019). Moreover, researchers have begun investigating the presence of eco-anxiety among undergraduate students, with the vast majority appearing to have high levels of eco-anxiety and stress over the earth’s state (Kelly, 2017).

Unfortunately, it is proposed that common psychological responses to eco-related distress – such as perceived lack of control, feelings of helplessness, and avoidant behaviours – hinder individuals’ ability to contribute to climate-change solutions (APA, 2017). On the contrary, when individuals personally relate the state of the climate to their own well-being, their motivation to engage in positive solutions increases (Sawitri, Hadiyanto, & Hadi, 2015, as cited in Government of Canada, 2019). If you thought about the effects of climate change on humans prior to reading this section, did mental health ever come to mind? What have your experiences with eco-anxiety been, if at all?

Treatments for Anxiety and Related Disorders

Many successful treatments for anxiety and related disorders have been developed over the years. Medications (anti-anxiety drugs and antidepressants) have been found to be beneficial for disorders other than specific phobia, but relapse rates are high once medications are stopped (Heimberg et al., 1998; Hollon et al., 2005), and some classes of medications (minor tranquilizers or benzodiazepines) can be habit forming.

Exposure-based cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT) are effective psychosocial treatments for anxiety disorders, and many show greater treatment effects than medication in the long term (Barlow, Allen, & Basden, 2007; Barlow, Gorman, Shear, & Woods, 2000). In CBT, patients are taught skills to help identify and change problematic thought processes, beliefs, and behaviors that tend to worsen symptoms of anxiety, and practice applying these skills to real-life situations through exposure exercises. Patients learn how the automatic “appraisals” or thoughts they have about a situation affect both how they feel and how they behave. Similarly, patients learn how engaging in certain behaviors, such as avoiding situations, tends to strengthen the belief that the situation is something to be feared. A key aspect of CBT is exposure exercises, in which the patient learns to gradually approach situations they find fearful or distressing, in order to challenge their beliefs and learn new, less fearful associations about these situations.

Typically 50% to 80% of patients receiving drugs or CBT will show a good initial response, with the effect of CBT more durable. Newer developments in the treatment of anxiety disorders are focusing on novel interventions, such as the use of certain medications to enhance learning during CBT (Otto et al., 2010), and transdiagnostic treatments targeting core, underlying vulnerabilities (Barlow et al., 2011). As we advance our understanding of anxiety and related disorders, so too will our treatments advance, with the hopes that for the many people suffering from these disorders, anxiety can once again become something useful and adaptive, rather than something debilitating.

Outside Resources

American Psychological Association (APA) http://www.apa.org/topics/anxiety/index.aspx

National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH) http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/anxiety-disorders/index.shtml

Web: Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA) http://www.adaa.org/

Web: Center for Anxiety and Related Disorders (CARD) http://www.bu.edu/card/

Discussion Questions

- Name and describe the three main vulnerabilities contributing to the development of anxiety and related disorders. Do you think these disorders could develop out of biological factors alone? Could these disorders develop out of learning experiences alone?

- Many of the symptoms in anxiety and related disorders overlap with experiences most people have. What features differentiate someone with a disorder versus someone without?

- What is an “alarm reaction?” If someone experiences an alarm reaction when they are about to give a speech in front of a room full of people, would you consider this a “true alarm” or a “false alarm?”

- Many people are shy. What differentiates someone who is shy from someone with social anxiety disorder? Do you think shyness should be considered an anxiety disorder?

- Is anxiety ever helpful? What about worry?

References

Albrecht, G. (2011). Chronic environmental change: Emerging “psychoterratic” syndromes. In I. Weissbecker (Ed.), Climate change and human well-being: Global challenges and opportunities (pp. 43–56). New York, NY: Springer.

Aikins, D. E., & Craske, M. G. (2001). Cognitive theories of generalized anxiety disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 24(1), 57-74, vi.

APA. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychological Association. (2017). Mental health and our changing climate: Impacts, implications, and guidance. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/20 17/03/m ental-health-climate.pdf

Anderson, C. A. (2001). Heat and violence. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 33–38. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00109

Antony, M. M., & Barlow, D. H. (2002). Specific phobias. In D. H. Barlow (Ed.), Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Arrindell, W. A., Eisemann, M., Richter, J., Oei, T. P., Caballo, V. E., van der Ende, J., . . . Cultural Clinical Psychology Study, Group. (2003). Phobic anxiety in 11 nations. Part I: Dimensional constancy of the five-factor model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(4), 461-479.

Barlow, D. H. (2002). Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Barlow, D. H., & Craske, M. G. (2007). Mastery of your anxiety and panic (4th ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Barlow, D. H. & Ellard, K. K. (2020). Anxiety and Related Disorders. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/xms3nq2c.

Barlow, D. H., & Liebowitz, M. R. (1995). Specific and social phobias. In H. I. Kaplan & B. J. Sadock (Eds.), Comprehensive textbook of psychiatry: VI (pp. 1204-1217). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins.

Barlow, D. H., Allen, L.B., & Basden, S. (2007). Pscyhological treatments for panic disorders, phobias, and generalized anxiety disorder. In P.E. Nathan & J.M. Gorman (Eds.), A guide to treatments that work (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Barlow, D. H., Ellard, K. K., Fairholme, C. P., Farchione, T. J., Boisseau, C. L., Allen, L. B., & Ehrenreich-May, J. (2011). Unified Protocol for the Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (Workbook). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Barlow, D. H., Gorman, J. M., Shear, M. K., & Woods, S. W. (2000). Cognitive-behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 283(19), 2529-2536.

Bogels, S. M., Alden, L., Beidel, D. C., Clark, L. A., Pine, D. S., Stein, M. B., & Voncken, M. (2010). Social anxiety disorder: questions and answers for the DSM-V. Depression and Anxiety, 27(2), 168-189. doi: 10.1002/da.20670

Borkovec, T. D., & Hu, S. (1990). The effect of worry on cardiovascular response to phobic imagery. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28(1), 69-73.

Borkovec, T. D., Alcaine, O.M., & Behar, E. (2004). Avoidance theory of worry and generalized anxiety disorder. In R.G. Heimberg, Turk C.L. & D.S. Mennin (Eds.), Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Advances in research and practice (pp. 77-108). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Borkovec, T. D., Hazlett-Stevens, H., & Diaz, M.L. (1999). The role of positive beliefs about worry in generalized anxiety disorder and its treatment. Clinical Psychology and Pscyhotherapy, 6, 69-73.

Boyer, P., & Liénard, P. (2008). Ritual behavior in obsessive and normal individuals: Moderating anxiety and reorganizing the flow of action. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(4), 291-294.

Bradley, B. P., Mogg, K., White, J., Groom, C., & de Bono, J. (1999). Attentional bias for emotional faces in generalized anxiety disorder. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38 ( Pt 3), 267-278.

Brown, T.A., White, K.S., & Barlow, D.H. (2005). A psychometric reanalysis of the Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43, 337-355.

Bruch, M. A., & Heimberg, R. G. (1994). Differences in perceptions of parental and personal characteristics between generalized and non-generalized social phobics. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 8, 155-168.

Bryant, R., Waters, E., Gibbs, L., Gallagher, H. C., Pattison, P., Lusher, D., . . . Forbes, D. (2014). Psychological outcomes following the Victorian Black Saturday bushfires. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 48, 634–643. doi:10.1177/0004867414534476

Canadian Mental Health Association’s BC Division (2013). Learn about panic disorder. Retrieved from https://www.heretohelp.bc.ca/sites/default/files/panic-disorder.pdf

Canadian Psychological Association (2015). “Psychology works” fact sheet: Phobias. Retrieved from: https://cpa.ca/docs/File/Publications/FactSheets/PsychologyWorksFactSheet_Phobias.pdf

Cannon, W.B. (1929). Bodily changes in pain, hunger, fear and rage. Oxford, UK: Appleton.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & National Center for Environmental Health. (2014). Impact of climate change on mental health. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/climate andhealth/effects/

Chiw, A., & Ling, H. S. (2019). Young people of Australia and climate change: Perceptions and concerns (Brief Report). Retrieved from https://www.millenniumkids.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Young-People-and-Climate-Change.pdf

Chorpita, B. F., & Barlow, D. H. (1998). The development of anxiety: the role of control in the early environment. Psychological Bulletin, 124(1), 3-21.

Clark, D. M. (1996). Panic disorder: From theory to therapy. In P. Salkovskis (Ed.), Fronteirs of cognitive therapy(pp. 318-344). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Clark, D. M. (1986). A cognitive approach to panic. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 24(4), 461-470.

Craske, M. G., & Barlow, D. H. (1988). A review of the relationship between panic and avoidance. Clinical Pscyhology Review, 8, 667-685.

Craske, M. G., & Barlow, D.H. (2008). Panic disorder and agoraphobia. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Craske, M. G., Antony, M. M., & Barlow, D. H. (2006). Mastering your fears and phobias: Therapist guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Drabant, E. M., Ramel, W., Edge, M. D., Hyde, L. W., Kuo, J. R., Goldin, P. R., . . . Gross, J. J. (2012). Neural mechanisms underlying 5-HTTLPR-related sensitivity to acute stress. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(4), 397-405. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111699

Dugas, M. J., Gagnon, F., Ladouceur, R., & Freeston, M. H. (1998). Generalized anxiety disorder: a preliminary test of a conceptual model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(2), 215-226.

Fullana, M. A., Mataix-Cols, D., Caspi, A., Harrington, H., Grisham, J. R., Moffitt, T. E., & Poulton, R. (2009). Obsessions and compulsions in the community: prevalence, interference, help-seeking, developmental stability, and co-occurring psychiatric conditions. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(3), 329-336. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08071006

Gelernter, J., & Stein, M. B. (2009). Heritability and genetics of anxiety disorders. In M.M. Antony & M.B. Stein (Eds.), Oxford handbook of anxiety and related disorders. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Government of Canada. (2019). Canada’s changing climate report. Retrieved from https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/sites/www.nrcan.gc.ca/files/energy/Climate-change/pdf/CCCR _FULLREPORT-EN-FINAL.pdf

Gunnar, M. R., & Fisher, P. A. (2006). Bringing basic research on early experience and stress neurobiology to bear on preventive interventions for neglected and maltreated children. Developmental Psychopathology, 18(3), 651-677.

Heimberg, R. G., Liebowitz, M. R., Hope, D. A., Schneier, F. R., Holt, C. S., Welkowitz, L. A., . . . Klein, D. F. (1998). Cognitive behavioral group therapy vs phenelzine therapy for social phobia: 12-week outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55(12), 1133-1141.

Hofmann, S. G., Alpers, G. W., & Pauli, P. (2009). Phenomenology of panic and phobic disorders. In M. M. Antony & M. B. Stein (Eds.), Oxford handbook of anxiety and related disorders (pp. 34-46). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hofmann, S. G., Lehman, C. L., & Barlow, D. H. (1997). How specific are specific phobias? Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 28(3), 233-240.

Hollon, S. D., DeRubeis, R. J., Shelton, R. C., Amsterdam, J. D., Salomon, R. M., O’Reardon, J. P., . . . Gallop, R. (2005). Prevention of relapse following cognitive therapy vs medications in moderate to severe depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(4), 417-422. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.417

Kelly, A. (2017). Eco-anxiety at university: Student experiences and academic perspectives on cultivating healthy emotional responses to the climate crisis. Unpublished manuscript.

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593-602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 617-627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617

Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Jin, R., Ruscio, A. M., Shear, K., & Walters, E. E. (2006). The epidemiology of panic attacks, panic disorder, and agoraphobia in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(4), 415-424. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.415

Lieb, R., Wittchen, H. U., Hofler, M., Fuetsch, M., Stein, M. B., & Merikangas, K. R. (2000). Parental psychopathology, parenting styles, and the risk of social phobia in offspring: a prospective-longitudinal community study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(9), 859-866.

McCabe, R. E., Antony, M. M., Summerfeldt, L. J., Liss, A., & Swinson, R. P. (2003). Preliminary examination of the relationship between anxiety disorders in adults and self-reported history of teasing or bullying experiences. Cognitive Behavior Therapy, 32(4), 187-193. doi: 10.1080/16506070310005051

McCabe, L., Cairney, J., Veldhuizen, S., Hermann, N., & Streiner, D. L. (2006). Prevalence and correlates of agoraphobia in older adults. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14, 515-522.

Myers, J. K., Weissman, M. M., Tischler, C. E., Holzer, C. E., Orvaschel, H., Anthony, J. C., . . . Stoltzman, R. (1984). Six-month prevalence of psychiatric disorders in three communities. Archives of General Psychiatry, 41, 959-967.

Neria, P., & Schultz, J. M. (2012). Mental health effects of hurricane Sandy characteristics, potential aftermath, and response. JAMA, 308, 2571–2572. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.110700

Osland, S., Arnold, P.D., & Pringsheim, T. (2018). The prevalence of diagnosed obsessive compulsive disorder and associated comorbidities: A population-based Canadian study. Psychiatry Research, 268. 137-142. doi: 10/1016/j.psychres.2018.07.018

Ost, L. G. (1992). Blood and injection phobia: background and cognitive, physiological, and behavioral variables. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101(1), 68-74.

Otto, M. W., Tolin, D. F., Simon, N. M., Pearlson, G. D., Basden, S., Meunier, S. A., . . . Pollack, M. H. (2010). Efficacy of d-cycloserine for enhancing response to cognitive-behavior therapy for panic disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 67(4), 365-370. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.036

Page, A. C., & Martin, N. G. (1998). Testing a genetic structure of blood-injury-injection fears. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 81(5), 377-384.

Pelletier, L., O’Donnell, S., McRae, L., & Grenier, J. (2017). The burden of generalized anxiety disorder in Canada. Health promotion and chronic disease prevention in Canada: Research, policy, and practice, 37, 54-62. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.37.2.04

Ranson, M. (2012). Crime, weather, and climate change. Harvard Kennedy School M-RCBG Associate Working Paper Series No. 8. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2111377

Rapee, R. M., & Melville, L. F. (1997). Recall of family factors in social phobia and panic disorder: comparison of mother and offspring reports. Depress Anxiety, 5(1), 7-11.

Sawitri, D. R., Hadiyanto, H., & Hadi, S. P. (2015). Pro-environmental behavior from a social cognitive theory perspective. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 23, 27–33. doi:10.1016/j.proenv.2015.01.005

Schneier, F. R., Leibowitz, M. R., Beidel, D. C., J., Fyer A., George, M. S., Heimberg, R. G., . . . Versiani, M. (1996). Social Phobia. In T. A. Widiger, A. J. Frances, H. A. Pincus, R. Ross, M. B. First & W. W. Davis (Eds.), DSM-IV sourcebook (Vol. 2, pp. 507-548). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

Shear, M. K., Brown, T. A., Barlow, D. H., Money, R., Sholomskas, D. E., Woods, S. W., . . . Papp, L. A. (1997). Multicenter collaborative panic disorder severity scale. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(11), 1571-1575.

Smoller, J. W., Block, S. R., & Young, M. M. (2009). Genetics of anxiety disorders: the complex road from DSM to DNA. Depression and Anxiety, 26(11), 965-975. doi: 10.1002/da.20623

Statistics Canada (2016). Threshold and subthreshold generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and suicide ideation (Catalogue no. 82-003-X). Health Reports, 27, 13-21. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/82-003-x/2016011/article/14672-eng.pdf?st=FYtORQ7Q.

Stein, M. B., & Kean, Y. M. (2000). Disability and quality of life in social phobia: Epidemiologic findings. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 1606-1613. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1606

Suárez, L, Bennett, S., Goldstein, C., & Barlow, D.H. (2009). Understanding anxiety disorders from a “triple vulnerabilities” framework. In M.M. Antony & M.B. Stein (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of anxiety and related disorders (pp. 153-172). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Wells, A. (2002). GAD, metacognition, and mindfulness: An information processing analysis. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice, 9, 95-100.